This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Yesterday’s letter mentioned the surprising resilience of China’s manufacture and export machine in the face of zero-Covid policies. Just as we pressed send, the latest PMI manufacturing survey for China landed and, naturally, showed a bigger-than-expected decline. Are things worse than we knew? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com & ethan.wu@ft.com.

What Powell said

Jay Powell said one new thing in yesterday’s speech: an as-clear-as-they-come hint that the Fed will raise interest rates by 50 basis points instead of 75 at this month’s meeting. In the same dovish vein, the Fed chair nodded to the fact that “my colleagues and I do not want to overtighten”. Stocks staged a 3 per cent rally.

But those marginally dovish remarks were tucked into a speech that, overall, was not bursting with optimism. Remember that a 50bp rate increase in December was already the odds-on favourite before Powell opened his mouth. Moreover, Powell made sure to downplay the importance of pacing of rates, as he did at last month’s meeting. What matters more than how fast rates rise, he reiterated, is the level at which they stop and how long they stay there. This is pretty unambiguous:

Cutting rates is something we don’t want to do soon, so that’s why we are slowing down.

He doesn’t want to cut rates anytime soon for the simple reason that inflation generally remains very high, though it is cooling a bit in some areas. So what would change Powell’s mind? He handed us three conditions yesterday:

-

Core goods prices need to keep falling.

-

CPI and PCE housing inflation need to follow private rent indices down.

-

Ex-housing core services inflation needs to fall decisively.

The first two conditions are just a matter of what is expected to happen happening. But the third condition, Powell insisted, hangs on how fast the labour market cools off:

Finally, we come to core services other than housing . . . this may be the most important category for understanding the future evolution of core inflation. Because wages make up the largest cost in delivering these services, the labour market holds the key to understanding inflation in this category . . .

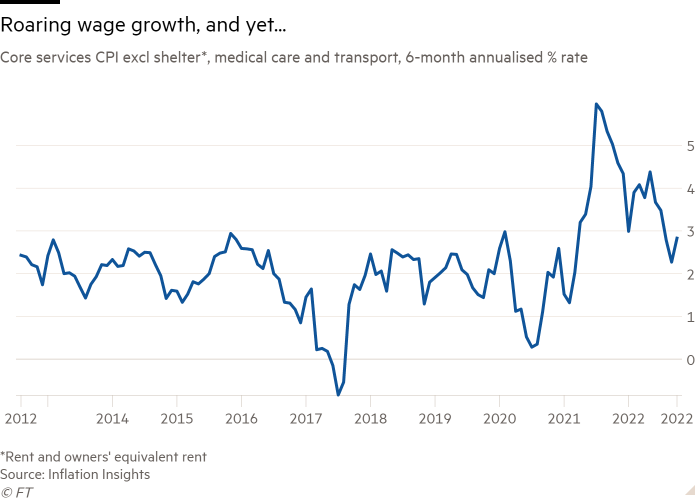

Not everyone agrees that core services ex-housing inflation is all about wages. Some specialists emphasise the role of wages in driving shelter inflation, but not necessarily in other categories. The chart of CPI inflation below illustrates the point. As we’ve discussed several times, this year’s jump in services prices came mostly from three areas — shelter (due to wages), medical care (largely due to a statistical quirk) and transportation (due to pent-up demand and pricey fuel). Strip those out and services inflation looks much tamer (chart courtesy of Omair Sharif at Inflation Insights):

Whether Powell is right about what drives inflation, markets will care about what he cares about, and he was plain that wage growth needs to fall and the labour market needs to weaken. Those are not the words of an inflation dove, nor of a man scared to risk a recession. (Ethan Wu)

Three ways the yield curve could be wrong

Compared with the stock market, which did a giddy little dance, the Treasury market responded to Powell’s comments with aplomb. Three-month yields were unchanged; two-year yields fell by a meaty 16 basis points, but 10-year yields fell by only five. In other words, Powell’s definitive message that rate increases will now proceed in half-percentage-point increments brought the medium-term outlook for policy rates down, but left the bigger picture looking a lot like it did before.

The big picture is that the yield curve, however you like to measure it, is as inverted as it has been in a very long time. For macroeconomic purposes, Unhedged likes to look at the 10-year/three-month curve. Here’s a chart:

The 10-year/two-year is even more inverted. All this has grabbed headlines this week. Here’s The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday:

Last week, the yield on the 10-year US Treasury note dropped to 0.78 percentage point below that of the two-year yield, the largest negative gap since late 1981, at the start of a recession that pushed the unemployment rate even higher than it would later reach in the 2008 financial crisis.

Still, many investors and analysts see reasons to think that the current yield curve may presage waning inflation and a return to a more normal economy, rather than an approaching economic disaster.

The current yield curve is “the market saying: I think inflation is going to come down,” said Gene Tannuzzo, global head of fixed income at the asset management firm Columbia Threadneedle … investors, he added, believe “the Fed does have credibility. Ultimately the Fed will win this inflation fight.”

Curve inversions are such reliable recession indicators (as the chart above shows) because long-term rates are determined by the market and are as such a very rough approximation of the equilibrium rate of interest for the economy. When the Fed pushes short-term rates above long-term rates, it is creating a significant drag on growth, increasing the odds of outright recession. The WSJ piece, however, is suggesting that the depth of the current inversion is, in part, a good sign: long rates are as low as they are because the market thinks the Fed will bring down inflation before too long.

But it’s not that much of a good sign: if the very credible Fed brings down inflation by causing a very credible recession, that will hurt. But might the yield curve be sending a false recession signal this time? There are two ways this could be true.

The first way is the “soft landing” view, or as we like to call it, “Waller’s dream”, after Fed governor Christopher Waller. He thinks that policy tightening could eliminate job openings, but not jobs, bringing the labour market into balance, slowing wages and bringing inflation to target. We have no idea how that would work. Chair Powell said yesterday that inflation could be controlled with “unemployment going up a bit but not really spiking”. That seems mighty tricky, too.

The second way the yield curve could be wrong is if the Fed is not a total hard-ass about inflation getting all the way to its official inflation target before starting to lower rates. Suppose that, instead of waiting for inflation to get to 2 per cent, the Fed began to ease with inflation in, say, the high 3’s — hoping to stave off a recession as growth falters. That would make it much more likely that a recession could be avoided.

Rick Rieder of BlackRock told us on Tuesday that something like this is his base case: “I think soft landing is very likely as long as the Fed doesn’t feel like it has to over tighten. Two-thirds of the economy is services and is not that rate-sensitive. You keep hammering at housing and auto finance, you are just creating more risk.” He thinks the Fed will pause rate increases relatively soon. For a pause (which is not to say a cut) “approaching the target over the medium term will be sufficient”.

The economist Olivier Blanchard argued in the FT this week that an inflation target of 3 per cent or so might be a good idea, as it would give monetary policy “more room to operate,” while at the same time not scaring everyone that central banks will let inflation get out of control. He writes:

I suspect that when, in 2023 or 2024, inflation is back down to 3 per cent, there will be an intense debate about whether it is worth getting it down to 2 per cent if it comes at the cost of a further substantial slowdown in activity. I would be surprised if central banks officially moved the target, but they might decide to stay higher than it for some time and maybe, eventually, revise it.

The Rieder/Blanchard picture is much more plausible than Waller’s tales of rate increases surgically excising job openings without touching jobs.

Of course, one must mention the third, opposite way that the yield curve could be wrong: long rates may be too low because the market is systematically underestimating how high rates will have to be, and how long, to stamp out inflation. In that case, the curve’s recession warnings are only wrong in that they are not loud enough.

One good read

A former VP at Amazon Web Services on the company’s attempts to make blockchain useful: “I’m not prepared to say that no blockchain-based system will ever be useful for anything. But I’m gonna stay negative until I see one actually at work doing something useful, without number-go-up greedheads clamped on its teats.”